Your Family Memoir Needs a Larger Context by Denis Ledoux

Please join me in welcoming memoir writer, Denis Ledoux, as he explains the pleasure associated with ghostwriting as an artist to create a living history that has style and deep, family meaning. Enjoy!

***

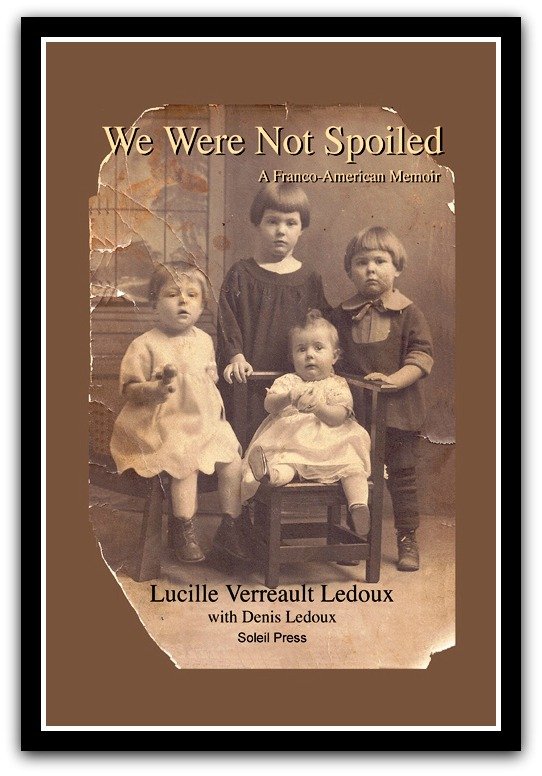

For the last four years, I was immersed in writing two memoirs of family members. The first was of my mother. This was a book that I undertook as a gift to my mother and to my family. The book that resulted was called We Were Not Spoiled and it covers the first thirty years of my mother’s life. Every time I visit her in her assisted living room and see it on her bureau top where she keeps it for display, I feel so satisfied with this accomplishment.

During much of the same time, I also ghostwrote a book for my uncle Robert Verreault. While I was generous with the time I billed him—generous much beyond what I would have permitted myself with a regular client, I was nonetheless working “for hire” on this project. The book that came of this collaboration was called Business Boy to Business Man.

1. The Memoir Writer as Artist

As a ghostwriter, you are an artist—or so I take myself to be—and work at creating a text which is a pleasure to read both for its style and for its meaning.

While you as an artist will clearly be limited by the subject’s ability to remember, willingness to share, and perspicacity, you will also be unbounded by your intuition about where to gently push your subject into deeper revelations, by flights of imagination in creating a world that once was, by offering insights the subject may not have been aware of. And of course, you are writing the best prose you can. Sometimes, because they are writing a family memoir, writers will presume they can get away with writing in less than a clear, concise and elegant style. Why shouldn’t a family memoir have the same standards any memoir destined for the public ought to have?

2. A Memoir Writer as Historian

It is hard to create historical context using only the subject’s material when the subject is not entirely aware of factors and dynamics that affected his/her life. “That’s just the way it was” may be a great posture for living a peaceful life, accepting difficulties and all of that, but it does not contribute to understanding a life trauma. Nor does “That’s what everyone was doing then” help you to understand much about the dynamics of this life you are chronicling.

Your task is to be the historian in this project. Of course, you are not seeking to record a history of any period. Instead, you are embedding a story in an historical context.

As in perhaps all memoirs that go outside the family’s reach, my two family memoirs needed to have an “everyman” and “everywoman” quality about them that went beyond the particularities of the lives lived. In other words, in what ways did their lives exemplify lives of their era, pick up on a gestalt. This historical context makes it possible for other people to understand the protagonists—and, one hopes, sympathize and identify with them.

3. How Could Two Siblings Be More Different?

My uncle Bob was an easy subject to place in an historical context. He had been with the US Navy in Iwo Jima during WW2 and had created a business—a machine shop—that had won him Maine Small Business Man of the Year in 1976—and significant financial rewards. He had traveled and, in later years, with the leisure his finances allowed, had become a reader. He had a clear sense of himself as being a player the world—albeit his was a small world—and of how that world and the large one beyond could learn something from him. He was a piece of cake.

As I was interviewing my mother, however, I was aware that there was much that she was saying that needed some context. Why was she doing what she did and what were choices at the time, choices she may have passed up for lack of ambition or fear of the new or being held back by culture and family?

My mother never asked herself these questions. Life was what life was.

Often there were historical contexts that, if the story were mine, I would easily provide to give a bigger picture. But the story was not mine. I had no trouble putting words in my mother’s mouth (as it were), but the memoir’s first person point of view seemed not to offer a vehicle for me to introduce historical content. Anyone who knew my mother (like my siblings!) would deny immediately that she had ever said such a thing—much less thought it.

My mother did give me tons of information. As she said in her book (this must be the truth as it’s in a book!), “I have always been able to remember names and date and information.” As a result, I did not feel the need to leave the first person in the narrative and go to the third. In addition, the third person opened up so many opportunities for the can-of-worms, “How do you know that” comments. After all, the third person clearly presumes an author who is not the protagonist.

4. Putting Words In My Mother’s Mouth and In The Footnotes.

What I ended up doing was placing in her voice what I felt she might have come up with and then placing other material in footnotes using my initials to identify their provenance. This kept the illusion of the memoir intact—the “I” of the protagonist and the “I” of the author are one and the same. In this way, I was able to place her in a context and make of her life something of an “everywoman” experience.

Using her voice and the footnotes, We Were Not Spoiled became a 208-page memoir that chronicles the first thirty years of my mother’s life in a larger context than it would have had I depended only on her stories as she told them. By adding words in her mouth and in the footnotes, I created an historical document that can be used in a classroom as well as read enjoyably by strangers—not to mention by my family who all seemed to love it. (No one told me otherwise!)

My uncle’s book? He remembered historical details sufficiently that all I had to do was look them up on the Net and make some corrections as to dates or official names, etc. He was off sometimes but basically he was spot on.

How can two siblings have been so different? Well, that’s another blog post.

Good luck ghostwriting a memoir!

***

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Denis Ledoux has been helping people to write memoirs since 1988 through his company The Memoir Network. He is now working on a high-school memoir tentatively titled In Another Century. He is the author of the classic Turning Memories Into Memoirs / A Handbook for Writing Lifestories. He lives, writes and works in Lisbon Falls, Maine. More at http://thememoirnetwork.com and http://thememoirnetwork.com/product-category/books-for-creating-better-memoirs/.

[…] people are free to write in more depth, deal more readily with past issues of painful or abusive childhoods, or write about controversial subjects when they write in the third person. […]