“Your novel would make a great movie! Why don’t you turn it into a screenplay?” by Jackie Blain

Today we welcome writing teacher and script consultant Jackie Blain as she shares with us her tips on adapting your novel into a screenplay. Would your novel make a great screenplay? Enjoy!

Today we welcome writing teacher and script consultant Jackie Blain as she shares with us her tips on adapting your novel into a screenplay. Would your novel make a great screenplay? Enjoy!

***

Have you heard someone say that about your work?

Or maybe you’ve been thinking the same thing. So why not give it a try?

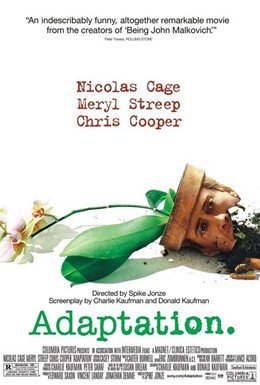

After all, there have been so many great movies made from novels: To Kill a Mockingbird, Silence of the Lambs, and of course the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

I say go for it… but first, take a deep breath and step back a second.

Prose and screenwriting are two very different genres and have different demands and joys and problems, not to mention formats.

I write (and teach) both, and it takes me a full day to switch my brain from one to the other. But it’s do-able. Absolutely! You can hire a screenwriter, of course, but if you want to give it a try yourself, here are seven things to think about when you tackle an adaptation.

-

You’ve only got 90-110 pages to tell the story.

That doesn’t seem so bad on the surface. But how long does it take to read a manuscript page? Three minutes? Ten? A screenplay rule-of-thumb is one page equals one minute of screen time, and it reads about like that as well. Which means adapting even a 100-page novella requires you to cut at least ¼ of the original material. Yikes! Now what?

-

First, find the spine and hang everything else off that spine.

What’s the dramatic question that needs to be answered by the end? Will boy-meets-girl end up with them together? Will the aliens take over the earth? In a script, the journey to the answer is the spine. One question—one answer. That means you may have to eliminate subplots, or scenes, or even characters… anything that doesn’t further the plot (or the theme as it grows out of the plot). Fran Walsh, Phillipa Boyens and Peter Jackson got a lot of flak when they left the Tom Bombadil sequence out of their LOTR script, but it wasn’t necessary, and with so little screen time available, something had to go.

-

Decide whose story it really is and stay with him/her.

If it’s Susie’s story, then that’s both your plot focus and your character focus. The hard part here is that you may have to eliminate other characters that you love, simply because they’re not as important to the main character and/or they don’t move the story forward. Poor Tom Bombadil…

-

Think “character function” rather than “character” when it comes to secondary characters.

If your heroine has both a best friend and a sister who serve basically the same function, you can merge them into one plucky side-kick. You’ll often have a more interesting character as a result.

-

A film story happens NOW.

Whatever happened in the past (backstory) may help us understand the characters and the story world’s history, but flashbacks and long expository conversations are dicey because they slow down the action. So you have to decide how much, and how, to reveal backstory.

-

Be prepared to revisit point of view.

Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games trilogy works so well because it’s in first person, present tense. We’re seeing and processing along with Katniss, and that’s one of the great things about novels: being able to immerse ourselves in another person’s reality. That’s hard to do with a script. You can either put your main character in every scene as a way to imitate first-person, or you can create new scenes to give us story information that she doesn’t have. The latter is what happened with the Hunger Games movie; I leave it to you to decide if it worked.

-

We can’t shoot emotions, feelings, or thoughts. We can only shoot actions.

This is absolutely the hardest thing for a novelist to wrap her head around. There’s an old screenwriting saying: if you can’t shoot it, you can’t write it in the script. That makes sense – the audience isn’t reading the script, they’re only watching action on a screen. Read Out of Sight (which is adapted from an Elmore Leonard novel) and you’ll see how Scott Frank turned thoughts into visuals. Not easy!

Don’t be afraid of adaptation.

Deciding what stays and what goes calls for artistic courage. But you truly are creating a new work, not just re-purposing an existing one. Give yourself permission to be ruthless, and you may just find yourself once again getting lost in the joy of creation.

***

Jackie Blain is a WGA member, writing teacher and script consultant who lives in Portland OR with the rain and two cats, and blogs about teaching and screenwriting.

Jackie Blain is a WGA member, writing teacher and script consultant who lives in Portland OR with the rain and two cats, and blogs about teaching and screenwriting.

Website: jackieblain.com

LinkedIn: Jackie Blain on LinkedIn

Twitter: @jackieblain