Use a Conflict Box to Sharpen Your Story by Kay Keppler

Let’s welcome back monthly columnist, editor, and novelist, Kay Keppler, as she shares with us “Use a Conflict Box to Sharpen Your Story.” Enjoy!

Let’s welcome back monthly columnist, editor, and novelist, Kay Keppler, as she shares with us “Use a Conflict Box to Sharpen Your Story.” Enjoy!

***

Most of the time if the plot of your story sags along the way, it’s a problem with your conflict. We all know what conflict is, but finding it sometimes can be surprisingly difficult.

A visual aid can help.

Let’s review the basics of conflict and see how a conflict box can help you see if your conflict is on track.

In the Beginning

Every story has a basic dynamic. It includes the:

- Protagonist, the character who owns the story, who struggles with the

- Antagonist, the character, who, if removed, removes the conflict, causing the story to collapse.

Next Comes Conflict

The protagonist and antagonist each pursue his/her concrete, specific goal, or external desire. (Note that the goal is not the motivation.)

Sometimes these goals are in opposition. At other times, these goals might be the same, but if one character achieves the desired goal, the other suffers.

Consequently, in pursuing their goals, the characters engage in conflict, which is a:

- Serious disagreement or argument

- Prolonged armed struggle

- Difference of opinion, principles, or interests

The conflict, no matter what kind of story you write, has life-or-death consequences for your characters as far as they’re concerned.

Define Characters Wisely

Your protagonist should be smart, funny, kind, interesting, or skilled—in short, someone your readers would like to hang out with. But s/he should have a flaw or blind spot—something that makes them un-perfect. Give him/her a unique voice, a strong motivation, and then put them in trouble.

Your antagonist must be as strong as your antagonist, with an equally strong goal and an equally strong will to pursue it.

The goals are difficult for the antagonist and protagonist to achieve because of external barriers, which are often each other. The reader must believe both will lose everything if they don’t defeat the other.

Choose a Strong Goal

If your conflict seems weak, be sure you understand the one thing the protagonist wants, how badly s/he wants it, what s/he’d do to get it, and how hard s/he fights the antagonist for it.

The goal must be a specific, concrete thing that s/he pursues throughout the story.

If s/he fails to achieve it, what happens? What are the stakes?

Try a Visual Aid

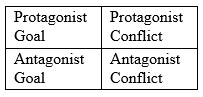

If your characters, their conflicts, and your story still aren’t coming together, try putting these elements in a conflict box to clarify what you’ve got and what might be missing.

It’s a way of diagramming the goals and conflicts of your protagonist and antagonist.

Here’s the basic setup:

How the Conflict Box Works

Let’s use Agnes and the Hitman by Jennifer Crusie and Bob Mayer for an example. In this story, Agnes has purchased Brenda’s house, but Brenda is scheming to take it away from her.

The protagonist (Agnes) and antagonist (Brenda) want the same thing—the house.

(The protagonist and antagonist could also want different things, and getting one goal conflicts with the other’s goal.)

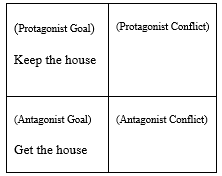

From Agnes and the Hitman, if we put the protagonist’s and antagonist’s goal in the conflict box, the box looks like this:

Agnes wants to keep her house, which she bought from Brenda.

Brenda wants to steal back the house that she sold to Agnes.

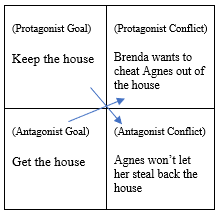

When we add the conflict, it looks like this:

The Conflict Lock

If your protagonist’s goal causes your antagonist’s conflict, and vice versa, that’s called a “conflict lock.”

If you have a conflict lock, you can know that your characters’ goals and conflicts are well aligned. Agnes and the Hitman has a conflict lock.

Draw a line from Agnes’s goal to Brenda’s conflict. If Agnes causes Brenda’s conflict, you’re halfway there.

Then draw a line from Brenda’s goal to Agnes’s conflict. If Brenda causes Agnes’s conflict, you have a conflict lock.

A conflict box can help you understand if you’ve sufficiently defined the characters’ goals and conflicts.

In addition, it can point out if your protagonist and antagonist are doing battle with each other, or if they merely have random trouble—or if several characters have conflicts with each other, diffusing the tension.

It’s fun to experiment with. Try it and see if it helps you.

(Many thanks to Michael Hauge, Jennifer Crusie, Bob Mayer, and all the other writing teachers who’ve demonstrated the conflict box.)

***

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kay Keppler is an author Zero Gravity Outcasts, Betting on Hope, Gargoyle: Three Enchanting Romance Novellas, and editor of fiction and nonfiction –Angel’s Kiss and Outsource It!

is an author Zero Gravity Outcasts, Betting on Hope, Gargoyle: Three Enchanting Romance Novellas, and editor of fiction and nonfiction –Angel’s Kiss and Outsource It!

She lives in northern California. Contact her here at Writer’s Fun Zone in the comments below, or at kaykeppler@yahoo.com to ask questions, suggest topics, or if you prefer, complain.

So Useful! Working on a “dynastic” thriller, read article and got to six boxes, with much clarity. Theme has lots of conflicts, and this is a good way to lead into scenarios.

Super helpful, thanks for the lesson.

Thanks! I’m so glad that the conflict box helped you resolve issues in your story. I’ve always found it to be very clarifying, especially when I run into trouble. It can really crystallize what you’ve written and help you see what’s going on with your conflicts.